This semester (Spring 2024), I took a class called “Critical Technical Practice” with Dr. Laura Devendorf, who heads up the Unstable Design Lab in the ATLAS building at CU. It was eye-opening, inspiring, and enjoyable from start to finish, particularly as someone who has little to no experience using design methods in research. I do a fair amount of design and art as a hobby, but like many researchers, it always felt to me like those things were destined to be separate, which was part of my inspiration for taking it in the first place. We got an expansive survey of critical design theory and methods, culminating in a month-long final project where we chose one or more methods to explore a topic of our choice. After learning about participatory design, speculative design, diegetic probes, design fiction, and many more approaches, I chose to focus on a combination of autoethnography, design memoir, and zines as alternative research communication.

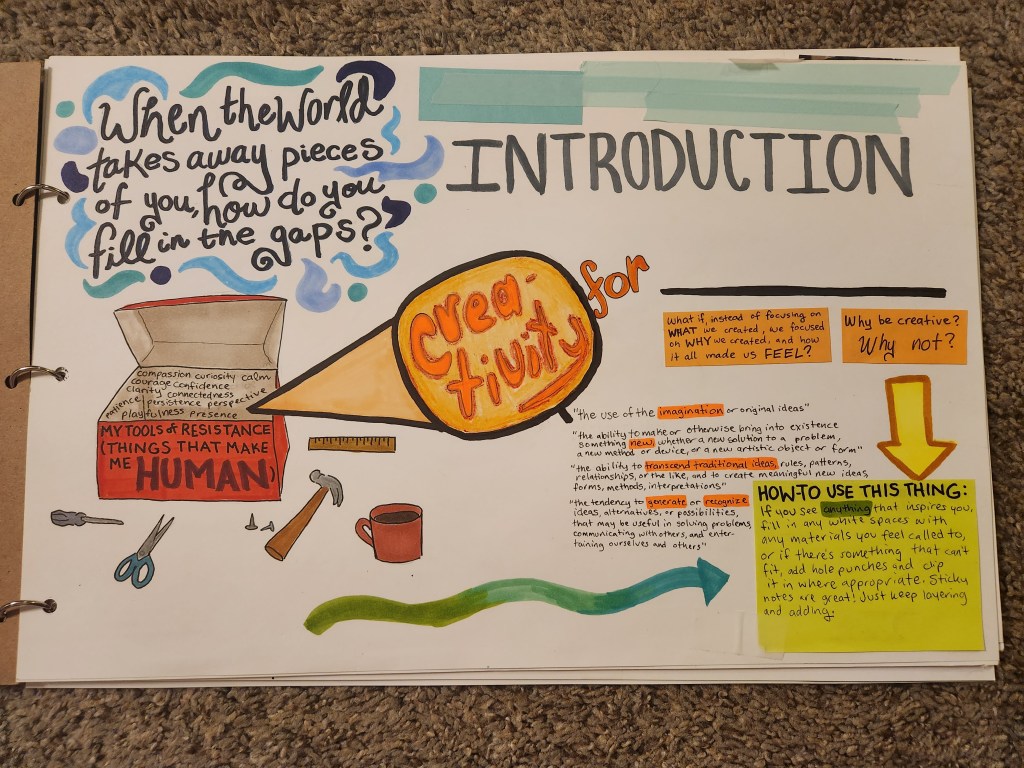

My objective for the final project project was to use an autoethnographic design memoir to create an artifact that expresses the feeling of fighting to be creative in an environment that suppresses creativity, with the secondary goal of provoking other people interacting with the artifact to think about themselves as creative beings. At first, I was inspired by the negative self-talk my diegetic probe participants [the midterm project for the class] expressed about their own creativity (or lack of it). I wanted to find a way to say, in essence, “if I can feel creative, so can you”. Communicating my own struggle to feel creative was the first component of that, and a lot of my struggle is the result of experiences with mental illness and mental healthcare. In line with that, the first iterations of my projects were very personal, and focused on lessons and coping mechanisms I have had to develop over the years to survive hardship and constraints. The second component (the “so can you”) was embodied in my final artifact, which took the most generative ideas from the autoethnography and strung them together into a collaborative workbook.

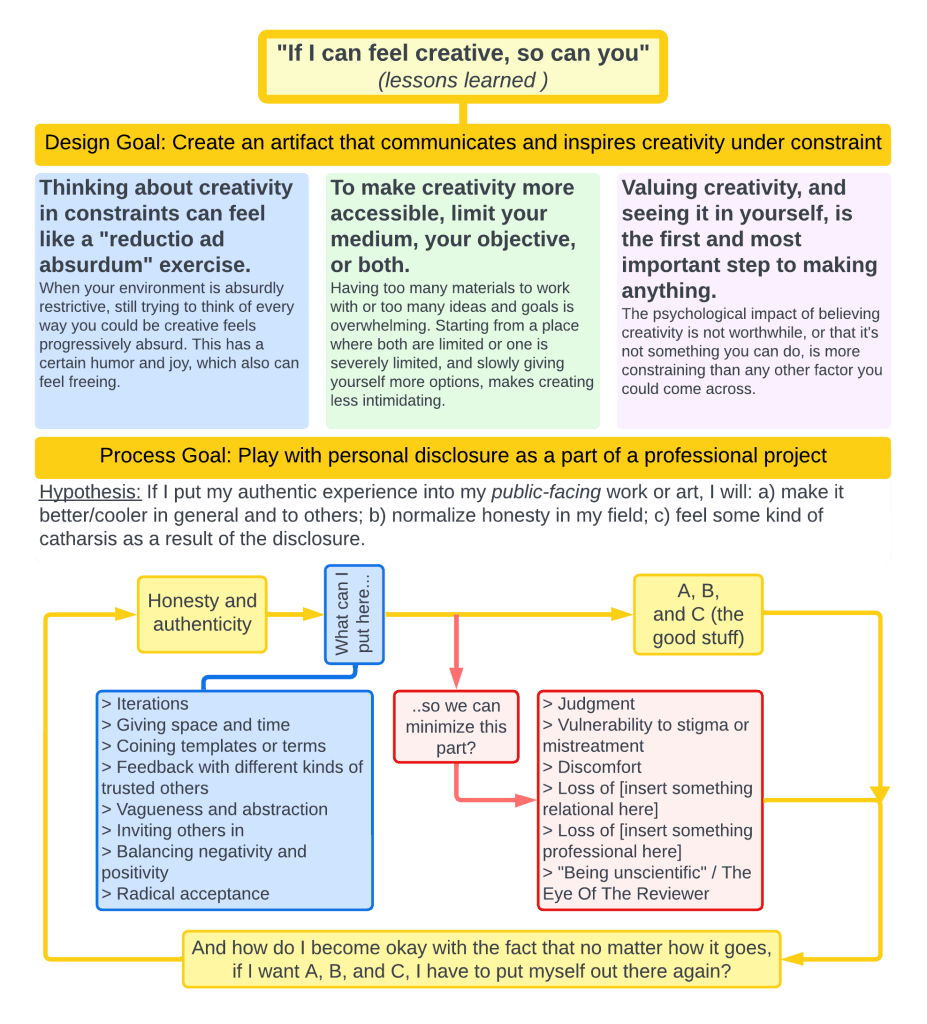

My design goal was to create an artifact that communicated and inspired creativity under constraint. As I iterated, I came to some provocations about what makes it easier to be creative when it feels like the last thing you’re capable of.

First, turning creativity into something like reductio ad absurdum can make it more accessible and joyful. While I was recovering from the concussion I got shortly after beginning the project, I couldn’t engage in cognition even as easy as a Monday crossword for more than fifteen minutes. During the first iteration I found myself not being able to stop thinking about ideas for the project, to the point where it was making me physically ill. It felt absurd: I was on a creative roll with a project that I had to stop so I wouldn’t become sick, but I still needed the creativity to return eventually. I ironically had to quickly think of any way I could to stop thinking about it. My gut reaction was to feel afraid, but embracing the absurdity of the situation and adapting my creativity accordingly made it fun and funny. This mirrors situations I’ve found myself in while managing my health: seemingly simple and mundane things become so difficult that adapting to them can feel imprisoning. Embracing creativity as an exercise in absurdity in these moments relieves some of the pressure.

Second, it takes practice to not become overwhelmed by too many ideas and materials when creating. In a truly constrained environment, creativity becomes necessary to survive. When things are less dire, devising low-stakes constraints for your creativity can make it easier to access. During the first iteration of the project, when my goal was still ambiguous, I limited myself in this way by working only with the paper within the binder. Similarly, although there was no pressure to end up with something polished or publishable, having a set amount of time in between iterations forced the creation of something, which, when it comes to creativity, is better than nothing.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, is having the psychological basis for creativity, made of two components: seeing creativity as important and seeing yourself as a creative being. I’ve always created art to cope with my struggles but didn’t always see myself as creative. At those times, I often felt ashamed of the art I made or berated myself for not being good at it. The mindset shifts to believe that all creativity is worthwhile, and that everyone is capable of it, helped release me from those negative secondary emotions. I hope that the materials I created for this project might be a starting point or an affirmation for others working through the same process.

A secondary goal I had was to play with personal experience and disclosure (roughly, autoethnography) as a part of a professional project, which I visualized above as a process of learning how to get the good from personal disclosure while avoiding the undesired.

The first two tools go hand in hand: iteration and giving space and time. Having emotional and chronological distance between you and the experiences you’re sharing before you actually share it provides necessary perspective. Iterating on a project can help build that distance. For this project, I started very emotionally and used materials created during difficult moments. I spent time with these most personal disclosures, and then I stepped back. I got feedback from people I trusted who were progressively less close to me (partner, friend, colleague, professor). As I moved further away from the emotional depths, I saw through others’ eyes and was able to simulate potential consequences without actually experiencing them. I could see more clearly where to balance negativity with positivity, to create corresponding balance in the emotions I might produce in others.I found places to protect myself with vagueness and abstraction (for example, referring to “health struggles” instead of saying what they were).

Through feedback, I also became aware that the best way to incentivize productive conversation around personal experience is to explicitly invite others in. While sometimes it makes sense for a disclosure to speak for itself (as context, for example), a generative design artifact has a level of impersonality that allows others to put themselves into the project. I also included specific prompts in my final iteration that I intended to be easy to answer, drawing the audience in.1 Coining a term or template (in this case, “creativity for ____”) was intended to make the project more memorable and catchier, but also to provide some structure for the audience to work off of.

Finally, I learned how important radical acceptance was to address the question I pose at the bottom of the diagram above: “How do I become okay with the fact that, no matter how it goes, if I want [positive consequences from disclosure], I have to put myself out there again?”. Radical acceptance in dialectical behavioral therapy is defined as “the ability to accept situations that are outside of your control without judging them, which in turn reduces the suffering that is caused by them.”2 There is no way to fully free yourself from things outside your control, like being misunderstood or judged for your experiences or identities in professional settings. If I do my best to control what I can control, using tools like what I outlined above, I can turn to radical acceptance not to condone stigmatizing reactions but to accept that they are a part of the process.

Images of my final project iteration can be found here.

1 This also was based on my experience being the social media manager for a student organization in undergrad, where I spent a lot of time designing content that would encourage our followers to interact productively. I wanted this to approximate an Instagram poll or similar, being quick and easy but still providing a gateway to engage more closely.

2 https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-radical-acceptance-5120614

Leave a reply to A Brief Post-Mortem on Two Years of PhD Life While Chronically Ill – Faye Kollig Cancel reply