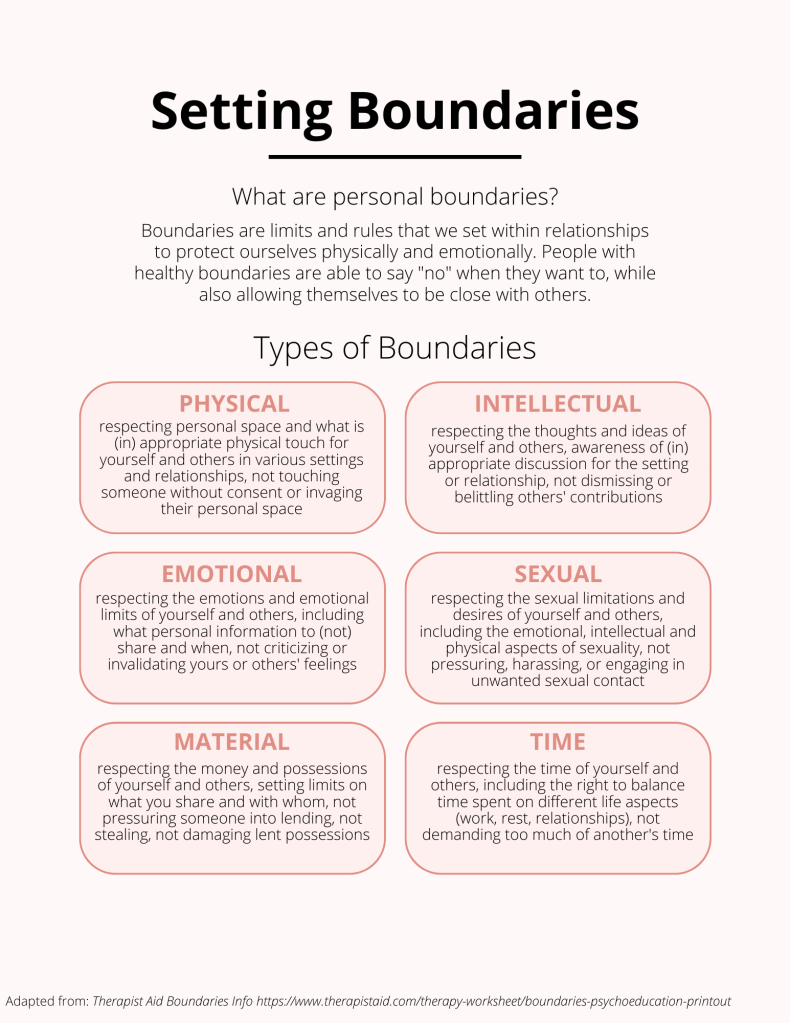

The picture above is a page from a mental wellness for grad students packet that I put together with a fellow doctoral student in my cohort. One specific kind of boundary that can include components from all categories is the oft-overlooked professional boundary. The most commonly discussed one is hours of work, or what time you are and are not available to do work tasks like responding to emails. Lately, I’ve been reflecting on what other boundaries and preventative care practices I use or aim to use in my professional life, and I thought I’d put together a list, with the goal of helping you (reader) reflect on and come up with your own.

- Always communicate what kind of help I want. Not only is this helpful for getting higher quality feedback, it can also be an important boundary setting practice where you also indicate what kinds of feedback you do not want. This can help protect you emotionally, intellectually, and relationally, avoiding the embarrassment, hurt, or wasted time of unwanted or unhelpful harsh critique. It also provides information that the people you rely on for help can use to communicate with you in general. Setting a norm that this conversation happens explicitly is also helpful for neurodivergent folks who might struggle with implied social rules.

- Give myself permission to not read relevant work if it’s triggering. A common side effect of working in academic research you find meaningful is that you’ll be reading and interacting with material that intersects with your identity and experience in potentially challenging ways. While some of this leads to great work, I always try to accept that there is nothing wrong with not reading a paper you might gain intellectually from if it is psychologically harmful for you to do so. This goes for research projects, too, not just reading. Don’t feel pressured to do things that trigger you or hit emotional distress buttons.

- Include casual conversations with coworkers and collaborators as “productive time”. Connection and off-the-calendar discussions are valuable, socially, emotionally, and intellectually. While it’s important to know when and how to have focus time, it’s also important to not label this form of work as “wasting time”. I try to seek out these conversations, especially with people I normally might not intersect with in terms of research topic, because it’s good for me, and it makes me a better researcher.

- Frame my needs as a fact, not a negotiation. These needs might be in any boundary category, but they are all vital to your success as a human being. Going into conversations with professors, advisors, and collaborators, I always try to establish that my limitations and needs (particularly in relation to my disability) are not a question of “asking for permission”. Needs come first; the work is shaped around it.

- Base my self-worth on many different things. I strive to not label my personhood in relation to my academic or professional “value”. This is true for everything, not just profession: I am not my publications, my schedule, my Zotero, my grades, or my workload. Nor am I my relationships, my hobbies, or my ethics. I’m all of it, which means one thing can’t hold complete power over my personal value. It’s sometimes hard to remember in the face of “failure” or disability, but it makes me a better researcher and a better person to keep a balanced view of myself.

These are just a few that work for me, but I would love to start a conversation about this. What factors make you a more balanced and fulfilled person? What factors actually improve your work?

Leave a comment